Answers to Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Various Billiards and Pool Topics

Categories

30-degree and 90-degree Rules

30-degree and 90-degree Rules for Cue Ball Control in Pool and Billiards

... how to predict cue ball motion to prevent scratches, aim break out shots, aim caroms, play position, and get through traffic.

30-degree rule

What is the 30-degree rule?

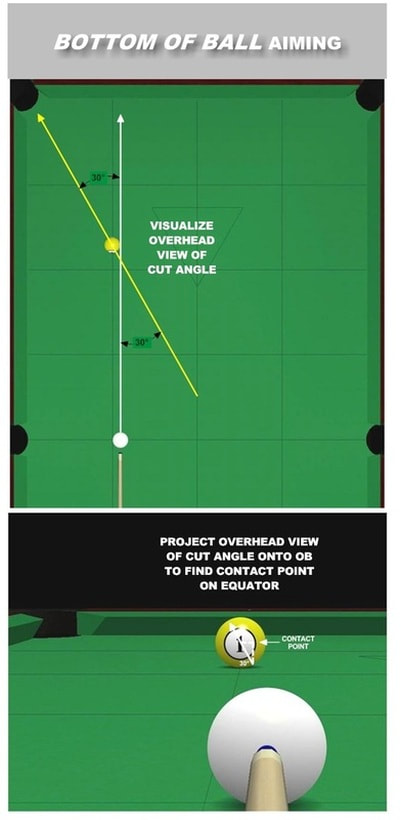

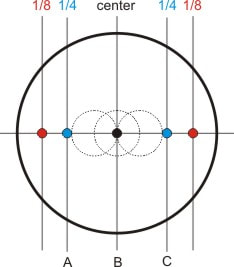

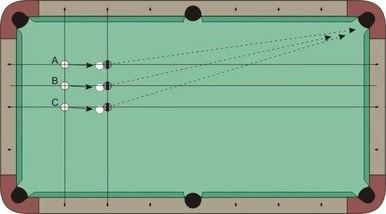

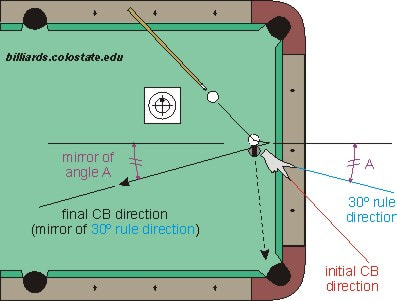

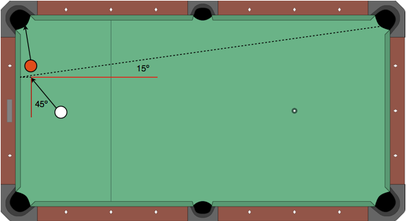

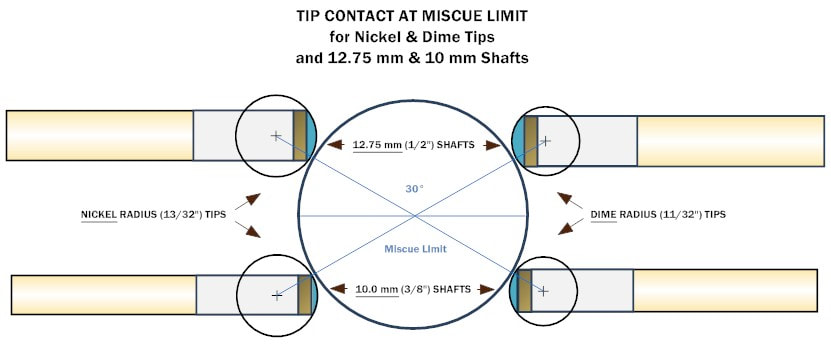

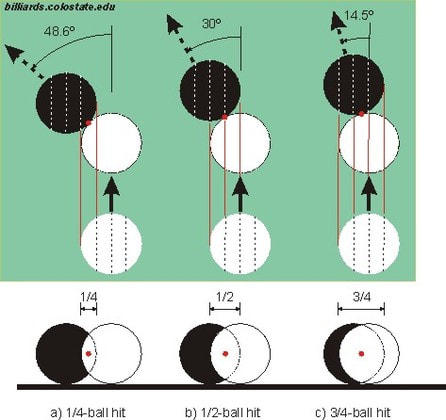

The 30-degree rule states that for a rolling-CB shot, over a wide range of cut angles, between a 1/4-ball and 3/4-ball hit, the CB will deflect by very close to 30° from its original direction after hitting the OB. If you want to be more precise, the angle is a little more (about 34 degrees) closer to a 1/2-ball hit and a little less (about 27 degrees) closer to a 1/4-ball or 3/4-ball hit. The rule is described and illustrated in the following video(YouTube)

... how to predict cue ball motion to prevent scratches, aim break out shots, aim caroms, play position, and get through traffic.

30-degree rule

What is the 30-degree rule?

The 30-degree rule states that for a rolling-CB shot, over a wide range of cut angles, between a 1/4-ball and 3/4-ball hit, the CB will deflect by very close to 30° from its original direction after hitting the OB. If you want to be more precise, the angle is a little more (about 34 degrees) closer to a 1/2-ball hit and a little less (about 27 degrees) closer to a 1/4-ball or 3/4-ball hit. The rule is described and illustrated in the following video(YouTube)

The Dr. Dave peace-sign technique is very useful in applying the 30-degree rule. Also, if you want to know how to account for speed effects, see "90° and 30° Rule Follow-up - Part V: the final chapter" (Download) (BD, June, 2005). And if you want to see how numbers change a little with typical pool equipment conditions, see "Rolling Cue Ball Deflection Angle Approximations" (Download) (BD, November, 2011).

Here a video demonstrations showing examples of how the 30-degree rule can be used in different shot situations:

Here a video demonstrations showing examples of how the 30-degree rule can be used in different shot situations:

The peace-sign technique can also be applied to draw shots using the trisect system.

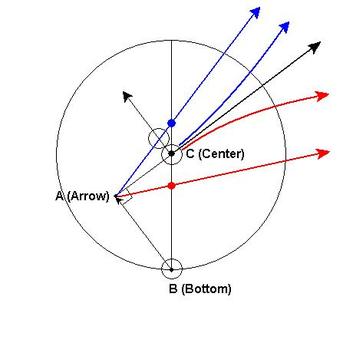

How can you tell if your peace-sign is the correct angle?

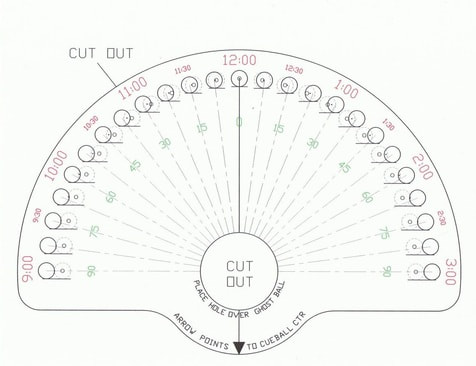

See NV B.44.(YouTube) Also, here's a template (Download) useful for learning how to apply the 30-degree rule accurately. The template can be used to help you train and calibrate your hand peace-sign (see "The 30° rule: Part I - the basics" (Download) - BD, April, 2004 and "90° and 30° Rule Follow-up - Part V: the final chapter" (Download) - BD, June, 2005).

One way to calibrate or check your peace sign at the table is to use your opposite hand index finger as a ruler to measure how much the tips of the "V" fingers should be spread. Using the 30-degree template (Download) or a 30-60-90 drafting triangle (available at office and arts and crafts stores), one can form the peace sign of the correct angles and then place the opposite-hand finger over the finger-tip gap, with the fingertip touching the tip of one of the fingers. Note where the second finger is relative to the other opposite-hand finger (e.g., just below the main knuckle, or at a certain wrinkle). Then (e.g., when you are playing), you can check your peace sign spread by recreating the same finger tip positions on your opposite hand.

Do people really use the 30-degree-rule peace-sign at the table?

If one has a critical shot close to a scratch, requiring precise caroms, needing ball break-up or avoidance, or with tight "traffic" of balls to negotiate, a well-calibrated peace sign can be extremely useful, allowing one to predict with confidence nearly exactly where the cue ball will go. One can adjust the peace sign slightly for the cut angle using the 30-degree rule angle template (external web-link) for help. One can also adjust for speed, as shown in "90° and 30° Rule Follow-up - Part V: the final chapter" (Download) (BD, June, 2005). Well-calibrated fingers can be much more accurate than intuition-based visualization.

How can you tell if your peace-sign is the correct angle?

See NV B.44.(YouTube) Also, here's a template (Download) useful for learning how to apply the 30-degree rule accurately. The template can be used to help you train and calibrate your hand peace-sign (see "The 30° rule: Part I - the basics" (Download) - BD, April, 2004 and "90° and 30° Rule Follow-up - Part V: the final chapter" (Download) - BD, June, 2005).

One way to calibrate or check your peace sign at the table is to use your opposite hand index finger as a ruler to measure how much the tips of the "V" fingers should be spread. Using the 30-degree template (Download) or a 30-60-90 drafting triangle (available at office and arts and crafts stores), one can form the peace sign of the correct angles and then place the opposite-hand finger over the finger-tip gap, with the fingertip touching the tip of one of the fingers. Note where the second finger is relative to the other opposite-hand finger (e.g., just below the main knuckle, or at a certain wrinkle). Then (e.g., when you are playing), you can check your peace sign spread by recreating the same finger tip positions on your opposite hand.

Do people really use the 30-degree-rule peace-sign at the table?

If one has a critical shot close to a scratch, requiring precise caroms, needing ball break-up or avoidance, or with tight "traffic" of balls to negotiate, a well-calibrated peace sign can be extremely useful, allowing one to predict with confidence nearly exactly where the cue ball will go. One can adjust the peace sign slightly for the cut angle using the 30-degree rule angle template (external web-link) for help. One can also adjust for speed, as shown in "90° and 30° Rule Follow-up - Part V: the final chapter" (Download) (BD, June, 2005). Well-calibrated fingers can be much more accurate than intuition-based visualization.

Half-ball hit "gems"

Why is a 1/2-ball hit (30 degree cut angle) so useful?

Here are some excellent videos Mike Page put together on half-ball hit "gems:"

NV B.6 - Mike Page's half-ball hit gems (part 1) (YouTube)

NV B.6 - Mike Page's half-ball hit gems (part 2) (YouTube)

and here's a good summary article from Bob Jewett (BD, November, 2000). (Download)

The "natural angle" effect associated with a half-ball hit is one of the most important principles in pool and billiards. It has always surprised me how little (if any) coverage is dedicated to these subjects in commercially-available pool and billiards books and videos. These effects have been understood at least as early as 1835 (see Coriolis' book under physics of billiards). Maybe if we keep writing articles and posting videos on these topics, maybe they will become more "mainstream."

Gem #4 from the videos is the basis of the 30-degree rule, which states that for a rolling CB, the deflected angle is very close to 30 degrees for all cut angles between 1/4-ball and 3/4-ball hits (not just a 1/2-ball hit). This gem is the single most important and useful principle in pool, especially when used in conjunction with the peace-sign technique.

Why is a 1/2-ball hit (30 degree cut angle) so useful?

Here are some excellent videos Mike Page put together on half-ball hit "gems:"

NV B.6 - Mike Page's half-ball hit gems (part 1) (YouTube)

NV B.6 - Mike Page's half-ball hit gems (part 2) (YouTube)

and here's a good summary article from Bob Jewett (BD, November, 2000). (Download)

The "natural angle" effect associated with a half-ball hit is one of the most important principles in pool and billiards. It has always surprised me how little (if any) coverage is dedicated to these subjects in commercially-available pool and billiards books and videos. These effects have been understood at least as early as 1835 (see Coriolis' book under physics of billiards). Maybe if we keep writing articles and posting videos on these topics, maybe they will become more "mainstream."

Gem #4 from the videos is the basis of the 30-degree rule, which states that for a rolling CB, the deflected angle is very close to 30 degrees for all cut angles between 1/4-ball and 3/4-ball hits (not just a 1/2-ball hit). This gem is the single most important and useful principle in pool, especially when used in conjunction with the peace-sign technique.

.Gem #4 is an interesting proposition demonstration with the carom shot from the foot rail. NV A.1 (YouTube) shows a similar "sure-thing" proposition. The following article also illustrates and discusses the shot in "The 30° rule: Part III - carom vs. cut" (Download) (BD, June, 2004).

TP A.1 (Download) and TP A.2 (Download) present an error analysis and look at the effects of table size.

Gem #2 is explained and illustrated in detail in "Draw Shot Primer - Part I: physics" (Download) (BD, January, 2006). The concept can also extended into the trisect draw-shot aiming system. This is also a very useful "gem."

Many additional resources, with lots of illustrations, examples, and video links related to these principle, can be found here:

The 1/2-ball hit is a common shot, especially in the game of 9-ball, where you need to move the CB around the table a lot. With a 1/2-ball hit, the CB easily be given enough speed to travel significant distance. The CB's motion can also be killed fairly easily with a 1/2-ball hit. Also, side spin is very effective off the cushions with a 1/2-ball hit. For thinner hits, the faster ball speed reduces the effect of the side spin; and for fuller hits and the resulting slower speed of the CB, the spin doesn't grab as well, especially on new cloth.

Largest deflected angle

Does the cue ball deflect the most for a half-ball hit?

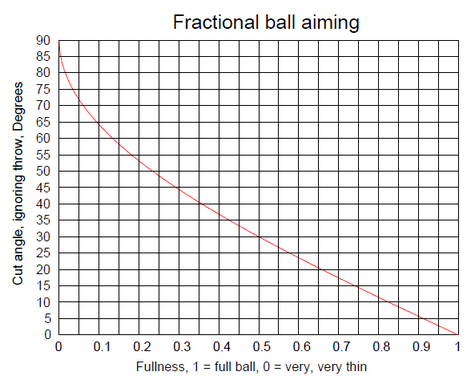

Close, but not precisely. See the bottom of TP 3.3. (Download) The maximum deflected angle (33.75 degrees) actually occurs at a cut angle of about 28 degrees, which corresponds to a 0.53 ball-hit fraction. These numbers are close to 30 degrees and a 1/2-ball hit, but not exact.

TP A.1 (Download) and TP A.2 (Download) present an error analysis and look at the effects of table size.

Gem #2 is explained and illustrated in detail in "Draw Shot Primer - Part I: physics" (Download) (BD, January, 2006). The concept can also extended into the trisect draw-shot aiming system. This is also a very useful "gem."

Many additional resources, with lots of illustrations, examples, and video links related to these principle, can be found here:

- 30-degree rule resource page (containing many additional resources and video demonstrations of how and when the rule is useful).

- collection of instructional articles on this topic: (Downloads)"The 90° rule: Part I - the basics" (BD, January, 2004).

- "The 90° rule: Part II - breakup and avoidance shots" (BD, February, 2004).

- "The 90° rule: Part III - carom and billiard shots" (BD, March, 2004).

- "90° and 30° rule review" (BD, July, 2004).

- "The 30° rule: Part I - the basics" (BD, April, 2004).

- "The 30° rule: Part II - examples" (BD, May, 2004).

- "The 30° rule: Part III - carom vs. cut" (BD, June, 2004).

- "90° and 30° Rule Follow-up - Part I" (BD, February, 2005).

- "90° and 30° Rule Follow-up - Part II: speed effects" (BD, March, 2005).

- "90° and 30° Rule Follow-up - Part III: inelasticity and friction effects" (BD, April, 2005).

- "90° and 30° Rule Follow-up - Part IV: sidespin effects" (BD, May, 2005).

- "90° and 30° Rule Follow-up - Part V: the final chapter" (BD, June, 2005).

- "Fundamentals - Part V: CB position control" (BD, January, 2009).

- "Fundamentals - Part VI: CB control examples" (BD, February, 2009).

- 30-degree rule and peace-sign technique one-page summary (Download) and the angle template. (Download)

- Math and physics backing up Gem #'s 2, 3, and 4 can be found in TP 3.3, TP A.4, and TP A.16. (Downloads)

The 1/2-ball hit is a common shot, especially in the game of 9-ball, where you need to move the CB around the table a lot. With a 1/2-ball hit, the CB easily be given enough speed to travel significant distance. The CB's motion can also be killed fairly easily with a 1/2-ball hit. Also, side spin is very effective off the cushions with a 1/2-ball hit. For thinner hits, the faster ball speed reduces the effect of the side spin; and for fuller hits and the resulting slower speed of the CB, the spin doesn't grab as well, especially on new cloth.

Largest deflected angle

Does the cue ball deflect the most for a half-ball hit?

Close, but not precisely. See the bottom of TP 3.3. (Download) The maximum deflected angle (33.75 degrees) actually occurs at a cut angle of about 28 degrees, which corresponds to a 0.53 ball-hit fraction. These numbers are close to 30 degrees and a 1/2-ball hit, but not exact.

Poetry

Are there easy ways to remember the 30 and 90 degree rules?

Here's some poetry:

30-degree rule:

If you let one finger stay,

The other finger points the way.

Peace.

90-degree rule:

When the ball has stun,

this is something you should not shun:

Point your finger, and the cue ball will follow the thumb.

If you do this, nobody will think you are dumb.

Are there easy ways to remember the 30 and 90 degree rules?

Here's some poetry:

30-degree rule:

If you let one finger stay,

The other finger points the way.

Peace.

90-degree rule:

When the ball has stun,

this is something you should not shun:

Point your finger, and the cue ball will follow the thumb.

If you do this, nobody will think you are dumb.

When the 30-degree rule applies

For what kinds of shots can the 30-degree rule be used?

The 30-degree rule is very useful for:

- scratch avoidance

- carom shot aiming

- cluster busting

- obstacle avoidance

- position play

- etc!

Here are some important things to keep in mind:

- the 30-degree rule applies only for natural roll shots.

- the 30-degree rule applies for the entire range of cut angles between 1/4-ball and 3/4-ball hits. This range includes the 1/2-ball hit (which is at the center of the range).

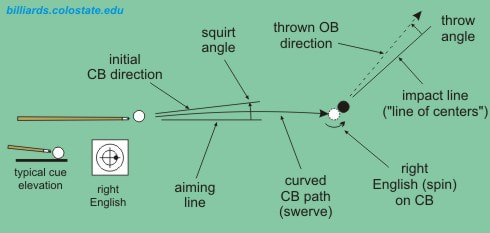

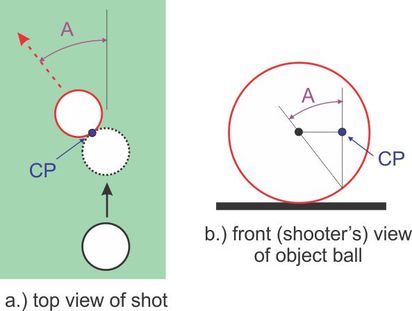

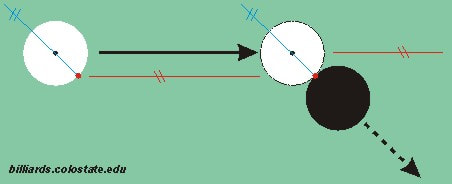

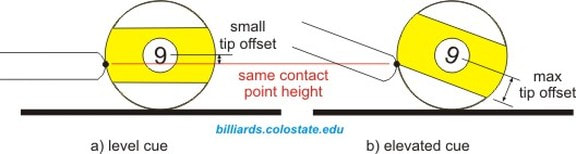

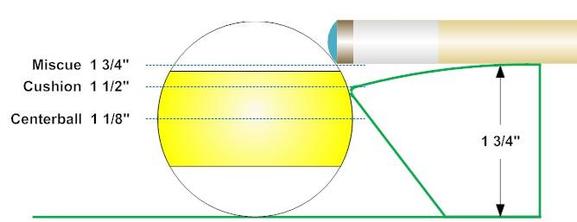

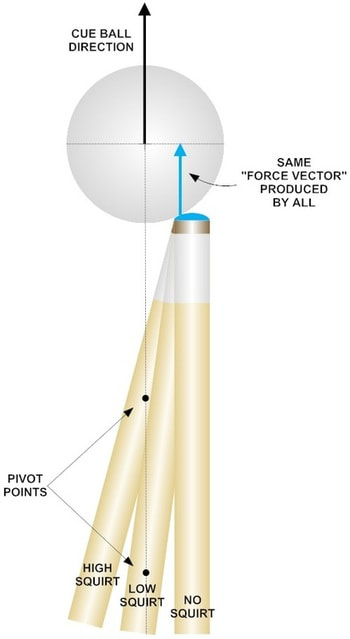

- the cue ball always leaves initially along the tangent line, which is 90 degrees away from (i.e., perpendicular to) the impact line (AKA object ball direction, line-of-centers, target line, etc.). However, for slow to medium speed natural roll shots, the cue ball deflects to the 30 degree direction almost immediately (i.e., the curve in the trajectory is almost imperceptible). Only at higher speeds does the travel down the tangent line become significant (e.g., see NV 3.8 (YouTube)). For more info, see the following demonstration from Disc I of the Video Encyclopedia of Pool Shots: (external web-link)

For what kinds of shots can the 30-degree rule be used?

The 30-degree rule is very useful for:

- scratch avoidance

- carom shot aiming

- cluster busting

- obstacle avoidance

- position play

- etc!

Here are some important things to keep in mind:

- the 30-degree rule applies only for natural roll shots.

- the 30-degree rule applies for the entire range of cut angles between 1/4-ball and 3/4-ball hits. This range includes the 1/2-ball hit (which is at the center of the range).

- the cue ball always leaves initially along the tangent line, which is 90 degrees away from (i.e., perpendicular to) the impact line (AKA object ball direction, line-of-centers, target line, etc.). However, for slow to medium speed natural roll shots, the cue ball deflects to the 30 degree direction almost immediately (i.e., the curve in the trajectory is almost imperceptible). Only at higher speeds does the travel down the tangent line become significant (e.g., see NV 3.8 (YouTube)). For more info, see the following demonstration from Disc I of the Video Encyclopedia of Pool Shots: (external web-link)

For more info, visit billiards.colostate.edu

Advice

Pool and Billiards Advice

... General advice about miscellaneous pool and billiards topics.

Alcohol effects

Why is it I sometimes play better when I drink alcohol?

First of all, you need to separate actual level of play from perceived level of play. Alcohol can affect both. For some people, a small amount of alcohol can actually increase relaxation and result in less tense (and better) play. For much more info, see "Beer-goggle effects" (Download) (BD, June, 2008).

Doing what feels "natural"

Should I do what feels natural, or try to change my stroke?

Concerning doing what is "natural," I don't think this is always the best advice. What many people do "naturally" doesn't always give the best results. For example, not dropping the elbow, or pausing in the final back swing, doesn't come naturally to many, but these changes can still help (some but not all people), even if it doesn't feel "natural." Now, with lots of practice, anything can be made to feel natural.

However, many people have stroke/stance/grip/bridge flaws that feel natural but cause inconsistency or inaccuracy. Sometimes, if these "natural" flaws are removed (through lots and lots of practice and maybe some instruction), improvement can result and the new technique (with the flaws removed) can become natural and relaxed (and more effective).

Improving your game

What can I do to make my game better?

The best way to improve is to practice (especially, if you work on your trouble areas. It might also help you to see an experienced and qualified instructor. They can often see problems or deficiencies with your mechanics and game that you might not know are there. They can also provide good advice for how to improve. Finally, if you haven't done so yet, you should read some books about pool. Improving your knowledge and understanding of the game might give you a wider arsenal of shots, help you be more creative at the table, help you be more aware of important factors for different types of shots, and help you improve with less practice.

from Bill Porter:

A couple of years ago I asked AZBers to single out the ONE IDEA that would most improve your pool game and they came up with a couple of dozen candidates. I narrowed those suggestions down to the eight you see below.

1. BE STILL over the shot, with as little movement of the head and body as possible.

2. STAY DOWN on the shot. Jimmy Reid once said he could tell who the good players were in a pool hall within a few minutes of entering the room. He said all he had to do was watch to see which players stayed down on their shots. Watching the cue ball contact the object ball is a good way to work on staying down on the shot as you stay down to watch the cue ball on its path to the object ball. This one is similar to #1, but deserves its own slot.

3. Treat EVERY SHOT with the same respect. "I quit missing those shots when I came to the realization that there is no such thing as an easy shot." (Luther "Wimpy" Lassiter)

4. Have a PRE-SHOT ROUTINE and follow it!

5. While standing up, decide on the shot (offense/defense, speed, side spin), then make a COMMITMENT to shoot the shot as you have decided to shoot it. Most shots are missed because of indecision. Another way to say this is to have a plan before every shot.

6. Do the highest percentage thing that YOU KNOW HOW to do (not what Efren would do).

7. Don?t let DISTRACTIONS cause you to lose focus on the shot. If something distracts you, stand up and go through your pre-shot routine from the beginning.

8. HAVE FUN! ? Your game may improve dramatically after reminding yourself that you are playing pool primarily to have fun.

Here's a suggestion for you. Take a small card, like a business card or an index card, and write a short version of the above suggestions on the card. Maybe the short versions would read something like this.

1) Be still

2) Stay down

3) Respect every shot

4) Follow the pre-shot routine

5) Commit to the shot

6) Play within your abilities

7) Defeat distractions, reset if necessary

8) Have fun!

Of course you may want to OMIT any of the 8 that really don't relate to your game. And you may want to ADD a few that are especially important for your game. Maybe you would add reminders to grip the cue lightly, pause at the end of your last back stroke, check your stance alignment, snug up your bridge, or whatever you have learned is useful for your game. If you carry that little card around with you, it will be handy to read over when you?re shooting poorly or in a slump.

From DeeMan, with a little humor thrown in:

Here are a few things to think about if you are really serious about improving and moving beyond banger status.

Some rules most don't have to think about but are impediments to playing well.

1) Don't shoot harder then you need for the shot and to gain position.

2) Know which direction your cue balls will go and think about how far it needs to travel.

3) Don't hit other balls on the table without a reason.

4) Learn to hit the center of the cue ball very precisely before worrying about hitting it off center.

5) Try not to leave the cue ball on a rail if not necessary.

6) Shoot balls first that clear the way for your other balls.

7) Identify packs and clusters and balls that won't "go" early and get a strategy to open then up or move them. To try to run out without this plan is foolish.

8) If you don't think you have a shot or safety you are playing Efren or just not looking hard enough.

9) Don't twirl the rack or do any other trick moves to impress people unless you are trying out for the circus.

10) Learn to stay level and shoot smoothly and don't think running boring balls rack after rack is something stupid or lucky.

11) Learn that draw and follow are for more than following or backing balls up.

12) Learn to "kill" the cue ball. NOTE: This does not involve a gun.

13) Don't put powder all over the table unless you are changing your opponent's diaper.

14) Don't show disappointment to your opponent when you mess up. That way, when you learn to intentionally miss, they won't know.

15) Don't whine, we have a guy named Earl that will handle that for you.

16) Chalk with your opposite hand.

17) Learn to read kisses. Not related to Madonna and Brittany.

18) Learn your limits and don't think your draw will all of a sudden resemble Cory's. That means learn to take your medicine and shoot the possible shot, the percentage shot.

19) Play the table (unless you are stalling).

20) Don't listen to guys on the internet giving you pool advice, especially DeeMan.

Selecting an instructor

How do I decide how to select an instructor?

I have met several "instructors" that were great pool players but terrible teachers. I have also met countless great players who would make terrible instructors. An instructor obviously must be knowledgeable and understand all of the intricacies of the game, and certainly have enough experience to appreciate those intricacies. An instructor must also be a good teacher and communicator and know how to connect with various types of people. Also, a great instructor should be a total "student of the game" (i.e., read everything, discuss and debate stuff on forums, communicate professionally and open-mindedly with other instructors and players, etc). Great instructors have too many things on their plate to be great players. To be a great player, one must have sharp eyes, a near-flawless stroke, and near-perfect speed control. That takes hours and hours of practice and play ... youth can also help. Only people completely dedicated to playing pool can put in the amount of time necessary to be great.

I don't think the true value a coach or instructor provides is information. Lots of great information can be found in good books and videos (and sometimes, even on the Internet). To me, the most important value an instructor offers is the ability and experience to work with a player as a unique individual, catering the instruction to best help that person improve.

FYI, a good list of well-respected and well-known instructors can be found here:

http://billiards.colostate.edu/links.html#Schools (external web-Link)

From Spider-man:

Talk to their former students. Ask them how the lessons were structured, did they feel it was worthwhile, and why. What was good, what was bad? Would they pay this instructor for more lessons in the future? Then ask yourself whether the described style of instruction is what you want.

Talk to as many as you can find, so that you're not captive to one person's glowing praise or damning complaint. You'll also learn how the instructor customizes his agenda to an individual student, or whether he has a "cookie-cutter" approach.

In other words, don't depend on the person selling you a service to tell you whether that service is good or bad. There's a huge temptation to tell you what you want to hear. Find the former students and get the story from the perspective of someone who was in the position you're about to be in. For a well-known instructor, or even a not-so-well known one that is local to you, there should be plenty of discussion available.

From Brian_in_VA:

I don't think a great teacher is necessarily a great player as they are two very different skill sets. Someone that is blessed with both is truly exceptional and may still not give a great lesson if the student isn't prepared to learn but then, that's the students fault.

A teacher has an abundant knowledge of the game, and knowledge of the mechanics for playing it properly and the willingness to share these.

A good teacher has that plus a methodology (often in the form of drills) for passing the knowledge to the student, for demonstrating the techniques and providing appropriate feedback to the student when first attempting them. This helps the student to build success with the new skill.

A great teacher has all that plus superior communication skills. This allows them to listen to the student, understand what the student is hearing and how they learn and then adapting their communication style to better fit that student. This provides a faster application of the new skill, a better cementing of it in the student's memory and a higher motivation to perform it correctly. The great teacher also assists the student in defining and developing reachable goals for their improvement. Without goals, there is little chance for long term success and application of what's been learned.

An excellent lesson, in my opinion, is 50% the responsibility of the student. If the student is anywhere above rank beginner, they should come prepared to learn with at least some idea of why they are taking a lesson, an initial goal, if you will. "I want to get better" is not a goal, it's a dream. "I want to improve my APA rating from a 4 to a 5" is better but it still is very results oriented. Best might be "I want to build a consistent enough stroke to be able to...."

What it takes to play like a pro

What does it take to play like a pro?

The main things top players have in common are:

... General advice about miscellaneous pool and billiards topics.

Alcohol effects

Why is it I sometimes play better when I drink alcohol?

First of all, you need to separate actual level of play from perceived level of play. Alcohol can affect both. For some people, a small amount of alcohol can actually increase relaxation and result in less tense (and better) play. For much more info, see "Beer-goggle effects" (Download) (BD, June, 2008).

Doing what feels "natural"

Should I do what feels natural, or try to change my stroke?

Concerning doing what is "natural," I don't think this is always the best advice. What many people do "naturally" doesn't always give the best results. For example, not dropping the elbow, or pausing in the final back swing, doesn't come naturally to many, but these changes can still help (some but not all people), even if it doesn't feel "natural." Now, with lots of practice, anything can be made to feel natural.

However, many people have stroke/stance/grip/bridge flaws that feel natural but cause inconsistency or inaccuracy. Sometimes, if these "natural" flaws are removed (through lots and lots of practice and maybe some instruction), improvement can result and the new technique (with the flaws removed) can become natural and relaxed (and more effective).

Improving your game

What can I do to make my game better?

The best way to improve is to practice (especially, if you work on your trouble areas. It might also help you to see an experienced and qualified instructor. They can often see problems or deficiencies with your mechanics and game that you might not know are there. They can also provide good advice for how to improve. Finally, if you haven't done so yet, you should read some books about pool. Improving your knowledge and understanding of the game might give you a wider arsenal of shots, help you be more creative at the table, help you be more aware of important factors for different types of shots, and help you improve with less practice.

from Bill Porter:

A couple of years ago I asked AZBers to single out the ONE IDEA that would most improve your pool game and they came up with a couple of dozen candidates. I narrowed those suggestions down to the eight you see below.

1. BE STILL over the shot, with as little movement of the head and body as possible.

2. STAY DOWN on the shot. Jimmy Reid once said he could tell who the good players were in a pool hall within a few minutes of entering the room. He said all he had to do was watch to see which players stayed down on their shots. Watching the cue ball contact the object ball is a good way to work on staying down on the shot as you stay down to watch the cue ball on its path to the object ball. This one is similar to #1, but deserves its own slot.

3. Treat EVERY SHOT with the same respect. "I quit missing those shots when I came to the realization that there is no such thing as an easy shot." (Luther "Wimpy" Lassiter)

4. Have a PRE-SHOT ROUTINE and follow it!

5. While standing up, decide on the shot (offense/defense, speed, side spin), then make a COMMITMENT to shoot the shot as you have decided to shoot it. Most shots are missed because of indecision. Another way to say this is to have a plan before every shot.

6. Do the highest percentage thing that YOU KNOW HOW to do (not what Efren would do).

7. Don?t let DISTRACTIONS cause you to lose focus on the shot. If something distracts you, stand up and go through your pre-shot routine from the beginning.

8. HAVE FUN! ? Your game may improve dramatically after reminding yourself that you are playing pool primarily to have fun.

Here's a suggestion for you. Take a small card, like a business card or an index card, and write a short version of the above suggestions on the card. Maybe the short versions would read something like this.

1) Be still

2) Stay down

3) Respect every shot

4) Follow the pre-shot routine

5) Commit to the shot

6) Play within your abilities

7) Defeat distractions, reset if necessary

8) Have fun!

Of course you may want to OMIT any of the 8 that really don't relate to your game. And you may want to ADD a few that are especially important for your game. Maybe you would add reminders to grip the cue lightly, pause at the end of your last back stroke, check your stance alignment, snug up your bridge, or whatever you have learned is useful for your game. If you carry that little card around with you, it will be handy to read over when you?re shooting poorly or in a slump.

From DeeMan, with a little humor thrown in:

Here are a few things to think about if you are really serious about improving and moving beyond banger status.

Some rules most don't have to think about but are impediments to playing well.

1) Don't shoot harder then you need for the shot and to gain position.

2) Know which direction your cue balls will go and think about how far it needs to travel.

3) Don't hit other balls on the table without a reason.

4) Learn to hit the center of the cue ball very precisely before worrying about hitting it off center.

5) Try not to leave the cue ball on a rail if not necessary.

6) Shoot balls first that clear the way for your other balls.

7) Identify packs and clusters and balls that won't "go" early and get a strategy to open then up or move them. To try to run out without this plan is foolish.

8) If you don't think you have a shot or safety you are playing Efren or just not looking hard enough.

9) Don't twirl the rack or do any other trick moves to impress people unless you are trying out for the circus.

10) Learn to stay level and shoot smoothly and don't think running boring balls rack after rack is something stupid or lucky.

11) Learn that draw and follow are for more than following or backing balls up.

12) Learn to "kill" the cue ball. NOTE: This does not involve a gun.

13) Don't put powder all over the table unless you are changing your opponent's diaper.

14) Don't show disappointment to your opponent when you mess up. That way, when you learn to intentionally miss, they won't know.

15) Don't whine, we have a guy named Earl that will handle that for you.

16) Chalk with your opposite hand.

17) Learn to read kisses. Not related to Madonna and Brittany.

18) Learn your limits and don't think your draw will all of a sudden resemble Cory's. That means learn to take your medicine and shoot the possible shot, the percentage shot.

19) Play the table (unless you are stalling).

20) Don't listen to guys on the internet giving you pool advice, especially DeeMan.

Selecting an instructor

How do I decide how to select an instructor?

I have met several "instructors" that were great pool players but terrible teachers. I have also met countless great players who would make terrible instructors. An instructor obviously must be knowledgeable and understand all of the intricacies of the game, and certainly have enough experience to appreciate those intricacies. An instructor must also be a good teacher and communicator and know how to connect with various types of people. Also, a great instructor should be a total "student of the game" (i.e., read everything, discuss and debate stuff on forums, communicate professionally and open-mindedly with other instructors and players, etc). Great instructors have too many things on their plate to be great players. To be a great player, one must have sharp eyes, a near-flawless stroke, and near-perfect speed control. That takes hours and hours of practice and play ... youth can also help. Only people completely dedicated to playing pool can put in the amount of time necessary to be great.

I don't think the true value a coach or instructor provides is information. Lots of great information can be found in good books and videos (and sometimes, even on the Internet). To me, the most important value an instructor offers is the ability and experience to work with a player as a unique individual, catering the instruction to best help that person improve.

FYI, a good list of well-respected and well-known instructors can be found here:

http://billiards.colostate.edu/links.html#Schools (external web-Link)

From Spider-man:

Talk to their former students. Ask them how the lessons were structured, did they feel it was worthwhile, and why. What was good, what was bad? Would they pay this instructor for more lessons in the future? Then ask yourself whether the described style of instruction is what you want.

Talk to as many as you can find, so that you're not captive to one person's glowing praise or damning complaint. You'll also learn how the instructor customizes his agenda to an individual student, or whether he has a "cookie-cutter" approach.

In other words, don't depend on the person selling you a service to tell you whether that service is good or bad. There's a huge temptation to tell you what you want to hear. Find the former students and get the story from the perspective of someone who was in the position you're about to be in. For a well-known instructor, or even a not-so-well known one that is local to you, there should be plenty of discussion available.

From Brian_in_VA:

I don't think a great teacher is necessarily a great player as they are two very different skill sets. Someone that is blessed with both is truly exceptional and may still not give a great lesson if the student isn't prepared to learn but then, that's the students fault.

A teacher has an abundant knowledge of the game, and knowledge of the mechanics for playing it properly and the willingness to share these.

A good teacher has that plus a methodology (often in the form of drills) for passing the knowledge to the student, for demonstrating the techniques and providing appropriate feedback to the student when first attempting them. This helps the student to build success with the new skill.

A great teacher has all that plus superior communication skills. This allows them to listen to the student, understand what the student is hearing and how they learn and then adapting their communication style to better fit that student. This provides a faster application of the new skill, a better cementing of it in the student's memory and a higher motivation to perform it correctly. The great teacher also assists the student in defining and developing reachable goals for their improvement. Without goals, there is little chance for long term success and application of what's been learned.

An excellent lesson, in my opinion, is 50% the responsibility of the student. If the student is anywhere above rank beginner, they should come prepared to learn with at least some idea of why they are taking a lesson, an initial goal, if you will. "I want to get better" is not a goal, it's a dream. "I want to improve my APA rating from a 4 to a 5" is better but it still is very results oriented. Best might be "I want to build a consistent enough stroke to be able to...."

What it takes to play like a pro

What does it take to play like a pro?

The main things top players have in common are:

- they have great vision and visual perception (i.e., they can clearly and consistently "see" the "angle of the shot" and the required line of aim).

- they have excellent "feel" for shot speed, spin, and position play.

- they are able to consistently and accurately deliver the cue along the desired line with the tip contact point and speed needed for the shot (even if their mechanics aren't always "textbook").

- they have tremendous focus and intensity and have a strong drive to improve and win

For more info, visit billiards.colostate.edu

Aiming

Aiming systems

How do different people aim?

"Fundamentals - Part II: aiming" (Download) (BD, October, 2008) and “Aim, Align, Sight - Part I: Introduction and Ghost Ball Systems” (Download) (BD, June, 2011) articles have some good illustrations and explanations related to aiming. See also: DAM aiming system. Aiming requires good visualization skills, precise body and cue alignment, accurate and consistent sighting, and an accurate and consistent stroke. And most importantly, it requires a lot of focus, and a lot of practice. There are no quick-fix solutions; although, "aiming systems" can help some people (for many reasons).

I personally use a combination of straight intuition (just "seeing the angle"), ghost-ball aiming, and contact point visualization (see DAM for more info). Bottom line: I just visualize the aim without using any kind of fractional-ball or fixed-reference compensation system. I certainly don't use any kind of math or numbers when I aim, like some people have suggested.

I think (but don't know) that if a scientific survey were done with all of the pro players, many (maybe even most) of them would say that aiming comes naturally (i.e., its "intuitive" or they just "see the angle"), because they have played so much. Some people might find the How the Pros Aim article (Download) interesting; although, it is not the result of a rigorous scientific study.

Here's a good introduction to aiming from Jerry Briesath. (YouTube)

from Patrick Johnson:

Many, maybe most, players learn to aim with no conscious technique, just by practice and repetition. Aiming techniques might make aiming easier for you, or you might be one of the many who use no technique. It isn't necessary to use them in order to play well. None of these techniques are better or worse than others, and it's not better or worse to use a technique or not. It's a personal choice.

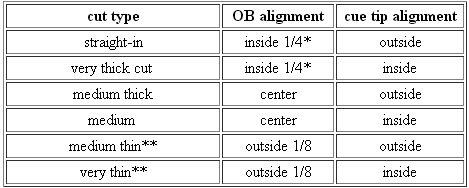

Two general categories of aiming techniques are:

1. "Exact" techniques produce exact aim in theory, but are limited by our imperfect ability to visualize and execute them. They include:

2. "Align & Adjust" techniques begin by aiming at the same part of the object ball each time (center, contact point or edge) and adjust from there "by feel" to the actual aim for the shot. Common beginning alignments are ("CB" = cue ball; "OB" = object ball):

from Spider man:

You are correct, that is a fine article. But, as even that author concludes, it will never be "put to rest". Luckily, it doesn't really matter. The numerous pros interviewed used a vast and disparate array of aiming techniques. "Ghost Ball" seemed to be the only somewhat-recurring assertion, but not to a dominant extent. There were even one or two who claimed to aim by "feel".

Personally I use the "ghost ball" technique most often, but not to exclusion of others. I learned to play with no coaching, and "ghost ball" was something I thought I invented . I didn't learn what everyone else called it until I read "99 Critical Shots". Now on some simple shots I just let the subconscious handle aiming - all I visualize is the desired result, and it happens, right down to how much the CB path distorts from the draw, and how far it rolls after the second rail. On very thin cuts I may visualize actual ball-to-ball contact points. But on ALL caroms I fall back to an augmented ghost-ball alignment. Most players will hit caroms too thick if they rely on feel.

What I would like to stress from that article is the one thing that everyone interviewed DID have in common - "the balls went in" for them.

The fact that so many different methods will work, and work well, ensures that some will die convinced that "their" way is "the only" way. Clearly all brains are not wired alike, and no one technique is ever going to be a panacea. Use what works for you, as long as it makes sense.

from Bob_Jewett:

You may find one of the following articles useful. I included the article about finding the center of the pocket because if you don't know where that is, it's pretty hard to aim well. (Downloads)

http://www.sfbilliards.com/articles/1993.pdf (June) -- close ball aiming

http://www.sfbilliards.com/articles/1996.pdf (February) -- frozen ball aiming

http://www.sfbilliards.com/articles/1997.pdf (April) -- finding the center of the pocket

http://www.sfbilliards.com/articles/1999.pdf (November) -- a smorgasbord of systems

http://www.sfbilliards.com/articles/2000.pdf (June) -- analysis of three systems

http://www.sfbilliards.com/articles/2004.pdf (June) -- ferrule system, lights system, overlap system

http://www.sfbilliards.com/articles/2004.pdf (December) -- aiming devices

http://www.sfbilliards.com/articles/2005.pdf (January) -- some more devices

http://www.sfbilliards.com/articles/2005.pdf (June) -- a history of parallel aiming

How do different people aim?

"Fundamentals - Part II: aiming" (Download) (BD, October, 2008) and “Aim, Align, Sight - Part I: Introduction and Ghost Ball Systems” (Download) (BD, June, 2011) articles have some good illustrations and explanations related to aiming. See also: DAM aiming system. Aiming requires good visualization skills, precise body and cue alignment, accurate and consistent sighting, and an accurate and consistent stroke. And most importantly, it requires a lot of focus, and a lot of practice. There are no quick-fix solutions; although, "aiming systems" can help some people (for many reasons).

I personally use a combination of straight intuition (just "seeing the angle"), ghost-ball aiming, and contact point visualization (see DAM for more info). Bottom line: I just visualize the aim without using any kind of fractional-ball or fixed-reference compensation system. I certainly don't use any kind of math or numbers when I aim, like some people have suggested.

I think (but don't know) that if a scientific survey were done with all of the pro players, many (maybe even most) of them would say that aiming comes naturally (i.e., its "intuitive" or they just "see the angle"), because they have played so much. Some people might find the How the Pros Aim article (Download) interesting; although, it is not the result of a rigorous scientific study.

Here's a good introduction to aiming from Jerry Briesath. (YouTube)

from Patrick Johnson:

Many, maybe most, players learn to aim with no conscious technique, just by practice and repetition. Aiming techniques might make aiming easier for you, or you might be one of the many who use no technique. It isn't necessary to use them in order to play well. None of these techniques are better or worse than others, and it's not better or worse to use a technique or not. It's a personal choice.

Two general categories of aiming techniques are:

1. "Exact" techniques produce exact aim in theory, but are limited by our imperfect ability to visualize and execute them. They include:

- Ghost Ball

- Double Offset

- Parallel Lines

2. "Align & Adjust" techniques begin by aiming at the same part of the object ball each time (center, contact point or edge) and adjust from there "by feel" to the actual aim for the shot. Common beginning alignments are ("CB" = cue ball; "OB" = object ball):

- CB Center to OB Center

- CB Center to OB Edge

- CB Center to OB Contact Point

- Stick Edge to OB Contact Point

from Spider man:

You are correct, that is a fine article. But, as even that author concludes, it will never be "put to rest". Luckily, it doesn't really matter. The numerous pros interviewed used a vast and disparate array of aiming techniques. "Ghost Ball" seemed to be the only somewhat-recurring assertion, but not to a dominant extent. There were even one or two who claimed to aim by "feel".

Personally I use the "ghost ball" technique most often, but not to exclusion of others. I learned to play with no coaching, and "ghost ball" was something I thought I invented . I didn't learn what everyone else called it until I read "99 Critical Shots". Now on some simple shots I just let the subconscious handle aiming - all I visualize is the desired result, and it happens, right down to how much the CB path distorts from the draw, and how far it rolls after the second rail. On very thin cuts I may visualize actual ball-to-ball contact points. But on ALL caroms I fall back to an augmented ghost-ball alignment. Most players will hit caroms too thick if they rely on feel.

What I would like to stress from that article is the one thing that everyone interviewed DID have in common - "the balls went in" for them.

The fact that so many different methods will work, and work well, ensures that some will die convinced that "their" way is "the only" way. Clearly all brains are not wired alike, and no one technique is ever going to be a panacea. Use what works for you, as long as it makes sense.

from Bob_Jewett:

You may find one of the following articles useful. I included the article about finding the center of the pocket because if you don't know where that is, it's pretty hard to aim well. (Downloads)

http://www.sfbilliards.com/articles/1993.pdf (June) -- close ball aiming

http://www.sfbilliards.com/articles/1996.pdf (February) -- frozen ball aiming

http://www.sfbilliards.com/articles/1997.pdf (April) -- finding the center of the pocket

http://www.sfbilliards.com/articles/1999.pdf (November) -- a smorgasbord of systems

http://www.sfbilliards.com/articles/2000.pdf (June) -- analysis of three systems

http://www.sfbilliards.com/articles/2004.pdf (June) -- ferrule system, lights system, overlap system

http://www.sfbilliards.com/articles/2004.pdf (December) -- aiming devices

http://www.sfbilliards.com/articles/2005.pdf (January) -- some more devices

http://www.sfbilliards.com/articles/2005.pdf (June) -- a history of parallel aiming

Benefits of various aiming systems

Why are some basic cut shot "aiming systems" helpful and effective?

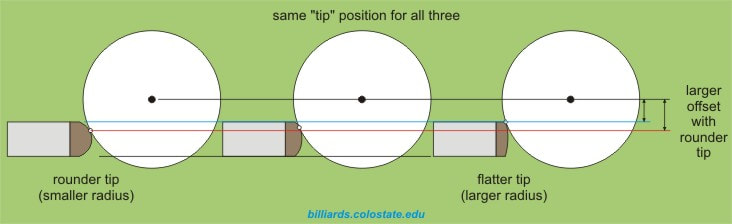

Any "system" that forces a person to focus on aim, alignment, and sighting consistently and with concentration will be beneficial to many people, especially people who currently don't focus well or long enough. It also helps to have a consistent and meaningful pre-shot routine, which the systems can help foster.

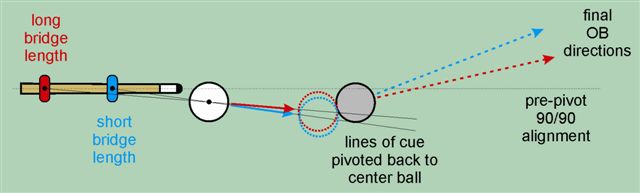

Concerning CTE, using the edge of the OB as a visual reference, and doing so consistently in setting up for every shot (e.g., by initially aligning with the CTE line), might help some people judge and visually learn/reinforce the amount of cut needed from one shot to the next. Also, focusing on the center of the CB (after the pivot) will help avoid unintentional side spin, which can cause squirt, swerve, and spin-induced throw, which can reduce accuracy and consistency. Also, placing the bridge hand down with the cue off angle (before the pivot) might allow some people to place their bridge hand more accurately because the pre-pivot cue might not disrupt the aiming line visual as much as when it is brought straight into the aiming line direction with the bridge.

From Colin Colenso (concerning 90/90 and CTE pivot-based systems):

I wanted to make a post listing what I perceive to be the strongest advantages of these systems.

I think these advantages are the main reason players often find great success aiming and shooting this way.

PLAUSIBLE CONTRIBUTING FACTORS:

1. Sighting point to point helps one to perceive an exact line and to take in the positions of the two balls relative to this line. In other words, they use a repeatable fixed method to visualize the ball positions.

2. These systems put you either right on line to begin with or in the ball park when used for appropriate shots.

3. In the pivot phase they move from this fixed line to another visual line that they perceive through the center of the CB. This finding of an aim line forces the mind to be decisive and exact. I believe forcing this decisiveness trains the mind not to wander and to make better decisions than just feeling around back and forth hoping to feel a ghost ball or contact point angle.

4. I suspect this one is the most powerful factor in these aiming methods. They force a player to commit to a pot line and then strike the cue dead straight through that line, rather than to swoop sideways on the shot as almost all beginners do. Because they focus hard on their pre-stroke alignment, they trust this line and stroke straight. If they do miss certain shots they will soon compensate with their aim until they learn to see the correct line. The normal player very often aims thick on their cut angles and swoops a little to make the cuts. When they try to bring speed or English into those shots they meet with many difficulties. So using any system that forces a player to adopt strict and accurate pre-alignment, followed by a straight stroke, should meet with considerable success and consistency after intensive practice.

5. Because players learn to trust their pre-alignment they begin to be able to relax during the actual stroke. This takes tension out of their arms and body and they can begin to execute with better speed and a more satisfactory feeling during execution. This may explain the feeling that they feel like they just pivot, bang and the ball goes in.

6. A system that requires a focus on the positioning of the cue may cause the player to be more highly aware of the line of cue. In standard aiming, some players may glance a little at the tip and CB but be mainly focused at the OB and therefore not getting much visual feedback from their cue, which is a straight line guide waiting to be used. Also, this cue position awareness may lead to a more constant positioning of the eyes over the cue. This is quite different to the normal play experience where there is a tendency to ride the ball into the hole. This occurs when players don't trust their alignment and tend to swoop a little to ride the cue ball to the correct point. This method of playing tends to make one have to work physically and mentally during the stroke. When pre-aligned well, the stroke is simply a matter of swinging the cue.

7. Using these systems may represent the most organized approach they have attempted for aiming. Several aspects have been compartmentalized so that each of these aspects can be focused on more clearly and developed individually. This organization may also assist in allowing the player to relax through the early implementation stage and then put their entire focus into the final alignment stage.

8. While sliding or shifting the cue into the final line of the shot, players may be incorporating a method that helps them to sight the required line of aim. This may be due to coming across the line, from left to right or vice versa, such that the sighter gets a feel for how the line of aim is moving relative to the position of the OB.

The only thing I don't agree with regarding these systems is that the systems find the aim line. I think it is the players that align themselves (via slight intuitive adjustments) to the correct aim line when need be. It will take them a little while to develop this ability for a wide range of shots.

From Mike Page (concerning pivot-based systems like CTE):

Various people report immediate improvement upon adopting a fractional ball approach. Others report immediate improvement upon adopting a "pivot" approach. Here's why. There are five independent "things" involved with aiming.

(1) the pocket

(2) the object ball

(3) the cue ball

(4) the stick

(5) the cyclopean eye

All 5 are necessary to get the job done. But the essence of determining the AIM LINE involves just three of these: the cyclopean eye, the cueball, and the object ball. The pocket should be considered BEFORE determining the AIM LINE The stick should be considered AFTER determining the aim line.

Many aiming perception problems involve, imo, either

(1) keeping the POCKET in the process too long or

(2) entering the STICK into the process too early

Those with problem (1) are helped by fractional ball approaches. Those with problem (2) are helped by pivot-style approaches.

A player MUST consider the pocket before determining the aim line. But once the pocket is considered to determine an object ball contact point or a ghost ball location or (along with the cue ball) a fullness of hit, there is no more information needed about the pocket. Many players suffer from being biased by the pocket when they're down on the shot. For those players, focusing on a ball overlap or on a cue ball aim point can help a lot.

Here's the other problem. When you are ready to pull the trigger, the STICK LINE and the AIM LINE are one and the same, and they need to be on the CORRECT AIM LINE. But before you are ready to pull the trigger, while you are just starting to get into position, all three are different. Imagine a red laser beam that is fixed on the CORRECT AIM LINE, and a green laser beam that is wherever you are looking, and a blue laser beam that goes through the center of the stick.

The CORRECT way to aim, imo, is first to get the green laser beam on the red one, and THEN to bring the blue one on board. If you don't do that, then you are biased by the stick line coming into view. The "almost right" stick line holds no value, but just like the fun-house almost straight walls and floors, we are drawn to them more than we should be.

So try aiming the shot by getting down into position with the stick off to the side and then with the ball-ball aim in view, bring the stick in from the side. Some people are helped a lot by this. It's a matter of not letting the tail wag the dog. So no, HOW you pivot doesn't matter. There are no magic rotating airpivoting receding hyperspheres. The emperor is naked.

From Mike Page:

If something seems to work or to help some people it IS important to many of us to understand WHY it helps. Part of this--most of us are here for fun when it comes down to it--is intellectual curiosity, but a big part of it is understanding what specific problems are solved by a particular approach to be able to incorporate and communicate those things directly and extend them to new situations.

There are reasons why beginning every shot the same way--looking full on or looking at the half-ball hit for instance--might be useful. The "SEEing it (from manual repetition)" you described above benefits from approaching the same shots the same way every time.

There are other reasons some of these approaches--whether it's one of Hal's methods or S.A.M. or whatever is being discussed here--help people. Get ready, because there's a big secret coming... These approaches cause people to do something they don't usually do. It's such an important thing that we have a name for it. It's called AIM. That's right.

If you look at the QUIET EYE studies, you will find one bit of consistency about the studies of pool, of putting, of basketball free throws, and of other aims involving stationary targets. Consistently a group of experts is compared to a group of wannabes. Consistently the group of experts GAZE at they target on average for a notably longer period of time in the "set" position. I'm talking maybe 2.5 seconds versus 1.5 seconds. It has become increasingly clear that this slightly longer gaze time--locking on your target for enough time-- is crucial for processing the information necessary to aim successfully.

Let's suppose many people suffer from inadequate GAZE time. IF true, then showing them a new method that forces them to lock in on the target (while following whatever the prescription is) will increase their success rate. Like the poop-on-the-swingset, the method might just be a mechanism to bring out the real solution (water/quiet-eye gaze time).

I point out in one of my aiming videos that I think another reason for any success people find with fractional ball aiming techniques is it causes them to sight parallel to the line the stick is moving. Many people don't. Many people sight from above the stick to the object ball contact point. This line is not parallel to the line of the stick or the cue ball motion.

Please understand that when someone suggests a method that SEEMS to not have the gaps filled in, that SEEMS to have shots that require two different angles to receive the same aim, that SEEMS to request the exact same aim for two sticks that we know squirt differently, it is like a giant bell going off for many of us.

Then if rather than taking off the system's clothes so that we can examine it honestly, the proponent points out that you really have to learn it in person or that such and such a world-class player uses it, it's like another giant bell going off.

... focusing on center-to-edge or edge-to-wherever gets your site line parallel to your stick. This could be a key for you to unlock the aim you really already have.

Or perhaps focusing on a shot from the edge of the cue ball and pivoting toward the center--like being discussed here--locks a person into an eye dominance that is different from what he would have done going straight down into the shot and gives him a perspective that works better for him.

My point is if these sorts of advice help certain people under certain circumstances pocket balls, then that's great. But it is very different from the aiming system "working." These people are actually finding their own aim; they're just approaching their own aim from a different angle.

From Joe W:

I suspect that aiming systems give people a reference point from which to think about the shot. Some players may or may not be aware of the idea that for some shots their subconscious makes adjustments.

On the one side aiming systems provide a zone of comfort for the player because they work in some (many) situations. This in turn leads to confidence when shooting and the player, over time, learns to compensate as needed.

On the other side it can be demonstrated that some aspects of these systems can not work as described. Proponents of the system seem to indicate that these systems take several weeks (?) to learn. However, the concepts are basically straightforward and could be briefly described and learned in a few hours. Weeks of training are required because the systems involve the development of "feel" though the user may not be aware of this aspect and therefore does not have to trust their natural sighting ability which is being developed within the system. For the present they have a system that can be relied upon.

In a sense, a player could be taught any of several systems and they all would work equally well if the player is willing to trust the system.

The conclusion is that one may seek the limits of the aiming system to learn what is useful for some particular shots from a physical basis and this may contribute to the development of a new, more advanced, system.

Why is aiming so difficult for some people?

Aiming is tough because it involves 3D visualization, visual perception, physical and visual alignment, and compensation for CIT (with no side spin) and/or squirt/swerve/throw with side spin.

From Patrick Johnson:

Aiming isn't a science, despite what some system [people] think. It involves many kinds of estimation:

- estimating where the OB contact point is by aligning it with the pocket, from a distance and an angle

- estimating how to adjust the OB contact point for throw

- estimating where the CB contact point is by imagining where it is on the "dark side" of the CB (this is part 1 of the subject of aiming systems)

- estimating how to align the CB and OB so the two contact points come together (this is part 2 of the subject of aiming systems)

- estimating how to position your head and eyes so all the above things are visualized correctly (this is part 2A of the subject of aiming systems)

This is only a partial list of the estimations required just for aiming (not stroking), and only for shots without side spin (don't get me started).

Even with a perfect stroke aiming isn't a simple, mechanically repeatable process.

From Colin Colenso:

I think that the biggest error that most players make when trying to become more accurate players is when they presume that their missed shots are caused by poor Stroke Mechanics, while they overlook the most common and significant cause which is poor Initial Alignment.

By Initial Alignment, I basically mean the positioning of the bridge point.

If you do not get your bridge to a point + or - a millimeter or less from the required line, then you are going to have to play an off center or sweeping stroke to pocket the OB as hoped.

In fact, it is common for players to subconsciously make this stroke adjustment when they feel that the shot is not going on line. This creates tension in their swing...their brain is fighting their heart is one way to describe it. So after they miss, they recall the sense of tension in the stroke, so confusedly start practicing their stroke, blaming their wrist action or some other aspect of stroke mechanics which is usually just a symptom of their poor Initial Alignment.

So to establish some proof for my contention, I set up a test.

A mechanical bridge was wedged into position. A piece of chalk sat under the rail as a firm point to keep the bridge from moving. CB and OB were put into positions that lined up for pocketing to the corner. Once established, I tapped the balls into place marked by a cross on the cloth. Hence I could replace the balls to almost identical positions each shot.

Using the bridge, fixed in place, my stroking did not feel very stable, yet I was able to pocket this shot 20 times in a row with very little variation in the pocketing accuracy. Not a single time did the OB hit the jaw.

Now I could make this shot miss by striking deliberately with English, but the point is, that it's not hard to hit the CB center ball accurately enough to provide satisfactory accuracy for most shots on the table.

The hard part is getting the bridge hand in perfect position for the shot...that is, to align perfectly

Why are some basic cut shot "aiming systems" helpful and effective?

Any "system" that forces a person to focus on aim, alignment, and sighting consistently and with concentration will be beneficial to many people, especially people who currently don't focus well or long enough. It also helps to have a consistent and meaningful pre-shot routine, which the systems can help foster.

Concerning CTE, using the edge of the OB as a visual reference, and doing so consistently in setting up for every shot (e.g., by initially aligning with the CTE line), might help some people judge and visually learn/reinforce the amount of cut needed from one shot to the next. Also, focusing on the center of the CB (after the pivot) will help avoid unintentional side spin, which can cause squirt, swerve, and spin-induced throw, which can reduce accuracy and consistency. Also, placing the bridge hand down with the cue off angle (before the pivot) might allow some people to place their bridge hand more accurately because the pre-pivot cue might not disrupt the aiming line visual as much as when it is brought straight into the aiming line direction with the bridge.

From Colin Colenso (concerning 90/90 and CTE pivot-based systems):

I wanted to make a post listing what I perceive to be the strongest advantages of these systems.

I think these advantages are the main reason players often find great success aiming and shooting this way.

PLAUSIBLE CONTRIBUTING FACTORS:

1. Sighting point to point helps one to perceive an exact line and to take in the positions of the two balls relative to this line. In other words, they use a repeatable fixed method to visualize the ball positions.

2. These systems put you either right on line to begin with or in the ball park when used for appropriate shots.

3. In the pivot phase they move from this fixed line to another visual line that they perceive through the center of the CB. This finding of an aim line forces the mind to be decisive and exact. I believe forcing this decisiveness trains the mind not to wander and to make better decisions than just feeling around back and forth hoping to feel a ghost ball or contact point angle.

4. I suspect this one is the most powerful factor in these aiming methods. They force a player to commit to a pot line and then strike the cue dead straight through that line, rather than to swoop sideways on the shot as almost all beginners do. Because they focus hard on their pre-stroke alignment, they trust this line and stroke straight. If they do miss certain shots they will soon compensate with their aim until they learn to see the correct line. The normal player very often aims thick on their cut angles and swoops a little to make the cuts. When they try to bring speed or English into those shots they meet with many difficulties. So using any system that forces a player to adopt strict and accurate pre-alignment, followed by a straight stroke, should meet with considerable success and consistency after intensive practice.

5. Because players learn to trust their pre-alignment they begin to be able to relax during the actual stroke. This takes tension out of their arms and body and they can begin to execute with better speed and a more satisfactory feeling during execution. This may explain the feeling that they feel like they just pivot, bang and the ball goes in.

6. A system that requires a focus on the positioning of the cue may cause the player to be more highly aware of the line of cue. In standard aiming, some players may glance a little at the tip and CB but be mainly focused at the OB and therefore not getting much visual feedback from their cue, which is a straight line guide waiting to be used. Also, this cue position awareness may lead to a more constant positioning of the eyes over the cue. This is quite different to the normal play experience where there is a tendency to ride the ball into the hole. This occurs when players don't trust their alignment and tend to swoop a little to ride the cue ball to the correct point. This method of playing tends to make one have to work physically and mentally during the stroke. When pre-aligned well, the stroke is simply a matter of swinging the cue.

7. Using these systems may represent the most organized approach they have attempted for aiming. Several aspects have been compartmentalized so that each of these aspects can be focused on more clearly and developed individually. This organization may also assist in allowing the player to relax through the early implementation stage and then put their entire focus into the final alignment stage.

8. While sliding or shifting the cue into the final line of the shot, players may be incorporating a method that helps them to sight the required line of aim. This may be due to coming across the line, from left to right or vice versa, such that the sighter gets a feel for how the line of aim is moving relative to the position of the OB.

The only thing I don't agree with regarding these systems is that the systems find the aim line. I think it is the players that align themselves (via slight intuitive adjustments) to the correct aim line when need be. It will take them a little while to develop this ability for a wide range of shots.

From Mike Page (concerning pivot-based systems like CTE):

Various people report immediate improvement upon adopting a fractional ball approach. Others report immediate improvement upon adopting a "pivot" approach. Here's why. There are five independent "things" involved with aiming.

(1) the pocket

(2) the object ball

(3) the cue ball

(4) the stick

(5) the cyclopean eye

All 5 are necessary to get the job done. But the essence of determining the AIM LINE involves just three of these: the cyclopean eye, the cueball, and the object ball. The pocket should be considered BEFORE determining the AIM LINE The stick should be considered AFTER determining the aim line.

Many aiming perception problems involve, imo, either

(1) keeping the POCKET in the process too long or

(2) entering the STICK into the process too early

Those with problem (1) are helped by fractional ball approaches. Those with problem (2) are helped by pivot-style approaches.

A player MUST consider the pocket before determining the aim line. But once the pocket is considered to determine an object ball contact point or a ghost ball location or (along with the cue ball) a fullness of hit, there is no more information needed about the pocket. Many players suffer from being biased by the pocket when they're down on the shot. For those players, focusing on a ball overlap or on a cue ball aim point can help a lot.

Here's the other problem. When you are ready to pull the trigger, the STICK LINE and the AIM LINE are one and the same, and they need to be on the CORRECT AIM LINE. But before you are ready to pull the trigger, while you are just starting to get into position, all three are different. Imagine a red laser beam that is fixed on the CORRECT AIM LINE, and a green laser beam that is wherever you are looking, and a blue laser beam that goes through the center of the stick.

The CORRECT way to aim, imo, is first to get the green laser beam on the red one, and THEN to bring the blue one on board. If you don't do that, then you are biased by the stick line coming into view. The "almost right" stick line holds no value, but just like the fun-house almost straight walls and floors, we are drawn to them more than we should be.

So try aiming the shot by getting down into position with the stick off to the side and then with the ball-ball aim in view, bring the stick in from the side. Some people are helped a lot by this. It's a matter of not letting the tail wag the dog. So no, HOW you pivot doesn't matter. There are no magic rotating airpivoting receding hyperspheres. The emperor is naked.

From Mike Page:

If something seems to work or to help some people it IS important to many of us to understand WHY it helps. Part of this--most of us are here for fun when it comes down to it--is intellectual curiosity, but a big part of it is understanding what specific problems are solved by a particular approach to be able to incorporate and communicate those things directly and extend them to new situations.

There are reasons why beginning every shot the same way--looking full on or looking at the half-ball hit for instance--might be useful. The "SEEing it (from manual repetition)" you described above benefits from approaching the same shots the same way every time.

There are other reasons some of these approaches--whether it's one of Hal's methods or S.A.M. or whatever is being discussed here--help people. Get ready, because there's a big secret coming... These approaches cause people to do something they don't usually do. It's such an important thing that we have a name for it. It's called AIM. That's right.

If you look at the QUIET EYE studies, you will find one bit of consistency about the studies of pool, of putting, of basketball free throws, and of other aims involving stationary targets. Consistently a group of experts is compared to a group of wannabes. Consistently the group of experts GAZE at they target on average for a notably longer period of time in the "set" position. I'm talking maybe 2.5 seconds versus 1.5 seconds. It has become increasingly clear that this slightly longer gaze time--locking on your target for enough time-- is crucial for processing the information necessary to aim successfully.

Let's suppose many people suffer from inadequate GAZE time. IF true, then showing them a new method that forces them to lock in on the target (while following whatever the prescription is) will increase their success rate. Like the poop-on-the-swingset, the method might just be a mechanism to bring out the real solution (water/quiet-eye gaze time).

I point out in one of my aiming videos that I think another reason for any success people find with fractional ball aiming techniques is it causes them to sight parallel to the line the stick is moving. Many people don't. Many people sight from above the stick to the object ball contact point. This line is not parallel to the line of the stick or the cue ball motion.

Please understand that when someone suggests a method that SEEMS to not have the gaps filled in, that SEEMS to have shots that require two different angles to receive the same aim, that SEEMS to request the exact same aim for two sticks that we know squirt differently, it is like a giant bell going off for many of us.

Then if rather than taking off the system's clothes so that we can examine it honestly, the proponent points out that you really have to learn it in person or that such and such a world-class player uses it, it's like another giant bell going off.

... focusing on center-to-edge or edge-to-wherever gets your site line parallel to your stick. This could be a key for you to unlock the aim you really already have.

Or perhaps focusing on a shot from the edge of the cue ball and pivoting toward the center--like being discussed here--locks a person into an eye dominance that is different from what he would have done going straight down into the shot and gives him a perspective that works better for him.

My point is if these sorts of advice help certain people under certain circumstances pocket balls, then that's great. But it is very different from the aiming system "working." These people are actually finding their own aim; they're just approaching their own aim from a different angle.

From Joe W:

I suspect that aiming systems give people a reference point from which to think about the shot. Some players may or may not be aware of the idea that for some shots their subconscious makes adjustments.

On the one side aiming systems provide a zone of comfort for the player because they work in some (many) situations. This in turn leads to confidence when shooting and the player, over time, learns to compensate as needed.

On the other side it can be demonstrated that some aspects of these systems can not work as described. Proponents of the system seem to indicate that these systems take several weeks (?) to learn. However, the concepts are basically straightforward and could be briefly described and learned in a few hours. Weeks of training are required because the systems involve the development of "feel" though the user may not be aware of this aspect and therefore does not have to trust their natural sighting ability which is being developed within the system. For the present they have a system that can be relied upon.

In a sense, a player could be taught any of several systems and they all would work equally well if the player is willing to trust the system.

The conclusion is that one may seek the limits of the aiming system to learn what is useful for some particular shots from a physical basis and this may contribute to the development of a new, more advanced, system.

Why is aiming so difficult for some people?

Aiming is tough because it involves 3D visualization, visual perception, physical and visual alignment, and compensation for CIT (with no side spin) and/or squirt/swerve/throw with side spin.

From Patrick Johnson: